This 182 year history, of what the Victorians called 'natural magic', begins in Lacock Abbey, Wiltshire in 1835 with Henry Fox Talbot making Britain's first ever photograph. As a frustrated, and poor, artist (his sketches were deemed 'melancholy to behold') he wanted to find a different, simpler, way to replicate nature. He inserted a piece of writing paper coated with a silver solution into a small wooden box. This produced a tiny negative from which a positive print could be made. This is the basic technique that remained in place until the dawning of the digital age.

Exposure times were two hours so it wasn't a speedy business. He was still working on improving the technique when, in 1837, he heard news from Paris. Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre was doing the same thing as him so Fox Talbot went public and, later, patented the process. From crude early works he soon grasped the concept of composition and framing as you can see from The Ladder and The Open Door. Works I think most of us would be happy with today.

Henry Fox Talbot - The Ladder

Henry Fox Talbot - The Open Door

The astronomer John Herschel called this new technique photography, Greek for 'light drawing', and soon others were taking it up. David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson, unusually working together, pioneered it as a medium for portraits as well as buildings. Frederick Scott Archer was a sculptor who wanted photos made of his works to help them sell. Wet plate photography was born reducing exposure time down to twenty seconds.

Mass production of these images became available, appropriate for the Industrial Revolution, and in 1854 at Bolton Abbey, Yorkshire's Roger Fenton became the founder of the Photographic Society who wanted to raise the status of photography to that of a fine art. Fenton's wonderful, and evocative, presentations of fishermen and ruins certainly helped that process along. One critic claimed Fenton to be the Turner of photography and his Pool below the Strid, like Turner, carried the influence of German romanticism. Unlike the painters though Fenton had to carry loads of heavy gear around with him including a portable dark room.

David Octavius Hill & Robert Adamson - Newhaven Fishermen

Roger Fenton - Abbey Ruins

Roger Fenton - Pool below the Strid, Bolton Abbey

Fenton was as much a realist as he was a romantic. He took photos of the Crimean War, the first ever war photography. Dust and heat spoiled many of the photos and dead men getting in his way hindered his progress (!) but the cannonballs lying in the lines between the British and Russian positions told an evocative story and, with his image of General Sir George de Lacy Evans, seems to have stumbled upon the psychological portrait. There's something in Evans's expression that suggests a man who's seen more than a man should see.

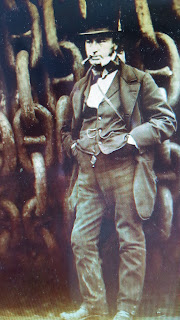

Contemporary Robert Howlett was more business minded (the Bond Street company he worked for wanted to make money after all). Isambard Kingdom Brunel paid Howlett to immortalise his huge Great Eastern steamship. The Illustrated Times bought the prints and got engravers to copy his images of the building process. You can see Brunel, below, in 1845 during the Great Eastern's problematic launch at a muddy shipyard in Millwall. By the time the Great Eastern had made her maiden voyage both Brunel and Howlett were dead.

Robert Howlett - Isambard Kingdom Brunel in front of the Great Eastern

Roger Fenton - De Lacy Evans

Roger Fenton - Cemetery on Cathcart Hill

Roger Fenton - The Valley of the Shadow of Death

Roger Fenton - Harewood House

After the Crimean War was over Fenton was commissioned to record the modernisation of Harewood House near Leeds. It must've felt quite some distance from Sebastapol and it clearly didn't satisfy his creative urges in the same way because two years later he retired from photography.

Commerce was taking over from art. High street shops had opened up in the 1850s that allowed ordinary people a chance, an affordable one too, to own a photograph of themselves. Even the neck clamping required to keep the subject's head in place didn't put prospective clients off. It was all the rage. People were loving it. Lady Eastlake observed that a photograph could be found both "in the most sumptuous saloon and in the dingiest attic".

Queen Victoria was more likely to be found in the latter. As a fan of the new medium she filled Osborne House and her other palaces with her collection. She was in even more. She became the most photographed woman of the century and she understood how she could use this to project and bolster her power. John Mayall's Carte-de-Viste sees Victoria and Alberts sans regalia, no crowns or emblems of state, in a blatant, yet successful attempt to engage with the people. When Albert died in 1861 William Bambridge and others took pictures that conveyed Victoria and her family in mourning. These were people just like us. They loved like us. They cried like us. Though we didn't get to live in palaces like them for some reason.

John Mayall - Carte-de-Visite

William Bambridge - Mourning Image

A reaction to this staidness, this control, and these manners, came in the form of Julia Margaret Cameron (to read about her life & V&A show click here). She lived with her husband in Dimbola Lodge, not far from Osborne House, on the Isle of Wight. 1864's Annie was a much more bohemian, even out of focus, work than people were used to at the time. Cameron saw beauty as far more important than clarity. With her portrait of the astronomer Herschel she was looking for psychological depth. She even went as far as to compare her taking of these photographs to prayer.

Julia Margaret Cameron - Annie

Julia Margaret Cameron - William Herschel

Julia Margaret Cameron - Mountain Nymph Sweet Liberty

Mountain Nymph Sweet Liberty took inspiration from the poetry of John Milton but later in the century Paul Martin found his themes in the more prosaic setting of Great Yarmouth. In 1892 he visited the Norfolk coastal resort with both his camera and some of the new ready made dry plates. No more portable dark room but many more portable cameras. Exposure times were now down to less than a second.

No tripod was required for these new fangled hand held cameras but shutters now were. With the advent of this technology came the age of the snapshot yet patience and temperament were still required for what Henri Cartier-Bresson called 'the decisive moment'. Paul Martin had both - and he also had the eye. His scenes from Great Yarmouth catch the Victorian working class both unguarded and at play.

Paul Martin - Courting couples on the beach at Yarmouth

Paul Martin - Couple on Yarmouth sands

Paul Martin - Girls paddling at Yarmouth beach

Peter Henry Emerson was more interested in the working aspects of working class life. Specifically the disappearing rural customs of the nearby Norfolk broads. His photographs of these bucolic businesses could almost have come from the brush of John Constable. Even Gathering Water Lilies, which at first seems idyllic, actually shows the boaters catching lilies for future use luring tench.

Peter Henry Emerson - Ricking the Reel

Peter Henry Emerson - Gunner working up to Fowl

Peter Henry Emerson - The old order and the new

Peter Henry Emerson - Gathering water lilies

Eamon's own Heysel stadium experience made him pretty well qualified to talk about photojournalism. In 1904 the Daily Mirror first exploited a new technique called halftone but it was on the 3rd January 1911, during the Sidney Street siege in East London, when it finally had its moment in the sun. Muzzy backgrounds and cropping were used to help tell the news to the paper's readers. The photographers weren't even given a credit. Winston Churchill got more out of it - becoming the first politician to exploit a photo opportunity like Queen Victoria had done decades earlier and other politicians would continue to do until the present day. He'd be wearing a hi-viz jacket and a hard hat now I expect.

Unknown photograpger - Sidney Street siege

Unknown photograpger - Sidney Street siege

Unknown photograpger - Sidney Street siege (with Winston Churchill)

Christina Broom was granted access to the Wellington Barracks and in the run up to World War I she succeeded in putting a human face on an increasingly inhumane world. Based in Fulham she sold her postcards in London's stationery shops and it wasn't just soldiers that sold. She turned her lens to other big events in the capital from the Boat Race to Suffragette rallies.

Christina Broom - Wellington Barracks

Christina Broom - Wellington Barracks

Christina Broom - 1914 Cambridge boat race crew

Christina Broom - Suffragettes

While she documented the home front others went to France, to the war. The soldiers, themselves, photographed the front line with their Vest Pocket Kodaks, a camera that had been marketed directly at the troops. It was about the size of a present day iPhone and came with a stylus that could be used for instant captioning of one's photos.

Poignant scenes of trench life mixed with images of billeted soldiers relaxing or playing sport. Some even caught action shots from the Western Front but, it's instructive to realise, the one that most upset the top brass was the picture of soldiers, supposed enemies, enjoying a game of football during the Xmas truce. The Vest Pocket Kodaks were banned. Fraternity with the enemy could not be encouraged. These soldiers were there to fight a war, and probably die, not make peace. And die they certainly did. 750,000 British troops perished before the end of the war in 1918. It seems likely that many of these photographs are the last photographs ever taken of many of these men.

Unknown photographer - World War I

Unknown photographer - World War I

Unknown photographer - World War I (Xmas truce)

As photojournalism was taking photography in one direction more artier styles were prevailing back in peacetime. Alvin Langdon Coburn, an American who'd moved to the UK as a young man, became the first celebrity photographer. He posed George Bernard Shaw as Rodin's Thinker, Yeats seemed to jump out of the picture at the viewer, and his image of Ezra Pound was boldly modern - and still looks so to this day.

Coburn didn't just do portraits. He thought London to be the most photogenic place in the world and his work there has echoes of Whistler's nocturnes and Hiroshige's woodcuts. As someone less concerned with the somewhat dry technical aspects of photographic practise and more in the art-historical narrative McCabe was weaving this particularly piqued my interest.

Alvin Langdon Coburn - George Bernard Shaw in the Pose of 'the Thinker'

Alvin Langdon Coburn - William Butler Yeats

Alvin Langdon Coburn - Ezra Pound

Alvin Langdon Coburn - London

Alvin Langdon Coburn - London

Alvin Langdon Coburn - London

The 1920s saw Cecil Beaton take the celebrity baton and run with it. He was to that decade's photography what F Scott Fitzgerald was to its literature and, like Fitzgerald, people were, and still are, unsure if he was critiquing or celebrating. Beaton was fascinated with the "bright young things" who used their inherited wealth to escape post war austerity and evaporate into hedonism (witness his sister Nancy as a shooting star in a cellophane sky). Beaton was both member and observer of this group and having it both ways won him a contract with Vogue.

Fashion magazines were following in the wake of newspapers and replacing drawings with photography. Beaton filled his aspirational pieces with chandeliers, lace, nods to Surrealism, and Italian fashion designers like Elsa Schiaparelli.

Cecil Beaton - Miss Nancy Beaton as a Shooting Star

Cecil Beaton - Elsa Schiaparelli

While they wiled away the hours in their ivory towers life in the 30s was very very different for those less well off. Hamburg born Bill Brandt turned his lens on the Jarrow marchers and the coal mining towns of the North East. As a foreigner he pretended to be curious rather than political but he was political alright. We all are.

Cobbled lanes in Halifax and coal miner's houses (with no fucking windows - this actually happened) in Durham tell of abject poverty, an underclass, and an almost sneering contempt from the governing classes about it. Despite the men (and sometimes women) in these photos being told where to sit by Brandt they tell a truth to power that needed to be told. These are amongst the most powerful peacetime photographs I've ever seen. The windowless houses are absolutely heartbreaking. I have to keep checking to see if they're real.

Bill Brandt - A snicket in Halifax

Bill Brandt - Coal Miner's Houses, East Durham

Bill Brandt - East Durham Coal Miner, just home from the pit

Bill Brandt - Northumbrian Coal Miner eating his evening meal

Brandt went on to work for Picture Post, launched in 1938, but it was another German émigré, Kurt Hutton, that summed up what that publication was all about. A paparazzi funfair shot of the working class at play. You can see her knickers now (you can see a fair bit more on the Internet too, I've heard) but in the 30s these were photoshopped out so as not to cause outrage.

A year later there were far more pressing concerns. World War II had broken out and Picture Post, which sold approximately 2,000,000 copies at its peak, started to march to a different beat. In 1945 Bert Hardy, and others, arrived at the liberation of Bergen-Belsen. Despite the horror they'd seen during the war they were completely unprepared for what befell their eyes. As anyone would be to witness the aftermath of the worst atrocity men have ever inflicted upon other men. It's hard to believe that George Rogers' picture of a young child walking nonchalantly along an avenue of corpses is a thing that ever actually happened. But it is - and it should never be forgotten. Lest we risk going there again.

Hardy was there to see Bergen-Belsen totally destroyed. As readers back home must've stared mouth agape in a state of shock at Life magazine when they published it I wonder what other stories, what other horrors never to be told, went up in blazes that day.

Kurt Hutton - Untitled

Bert Hardy - Untitled

Bert Hardy - Untitled

Unknown photographer - Bergen-Belsen

Unknown photographer - Bergen-Belsen

George Rogers - Bergen-Belsen

George Rogers - Bergen-Belsen

It's quite a jump from concentration camps to holiday camps so you can see why the producers decided to end the second programme with the end of the war and kick off the final segment with peace - and colour. John Hinde, like John Major, had failed in the circus business but, from 1957, succeeded in the postcard one. For him it was all about colour. Already vivid colours were manipulated until they became lurid - yet somehow still inviting. This was moving towards an era of photography I caught the back end of and when McCabe spoke about the domestic slideshow I had my own Proustian moment.

John Hinde - Giant's Causeway

John Hinde - Motor Racing at St.Ouen's Bay, Jersey, C.I

John Hinde - The Beach, Instow, North Devon

John Hinde - Trafalgar Square Fountains, London

John Hinde - The Inner Harbour, Ramsgate

I still want to go to THAT Ramsgate and THAT London now. That beach in North Devon too, of course. When, in 1963, Kodak introduced the cheap instamatic camera John Bulmer decided to push colour photography even further. Colour had always been seen as frivolous whilst black'n'white was used for grown up subjects. With a series commissioned by The Sunday Times Bulmer questioned and challenged the notion of monochrome as the only medium fit for serious reportage.

John Bulmer - The Curators

John Bulmer - Untitled

Observer photographer Jane Bown wasn't so convinced by colour. She refused to use it. To my mind that's a pity. There's no denying her shots of Nureyev and Hockney are wonderfully composed but I think colour would've improved, not harmed, them. Bown was a woman very sure of her own mind though. She took very little notice of the swinging 60s that surrounded her and, notoriously, wasn't even sure exactly who John Lennon and Paul McCartney were when she was dispatched to take their photos.

Jane Bown - Rudolf Nureyev

Jane Bown - John Lennon

Jane Bown - Paul McCartney

Jane Bown - David Hockney

So far. So white. This wasn't reflecting Britain's increasingly racial make up. In the 1970s the proudly independent Vanley Burke emerged in Birmingham. He'd come there from Jamaica and wanted to document the black British experience from the inside. He wasn't interested in selling his work to the papers or to art dealers. Instead he exhibited in local churches and schools and provided a powerful counterpoint to the corrosive, and untrue, dominant negative narrative of the era's black experience.

Vanley Burke - Untitled

Vanley Burke - Untitled

Vanley Burke - Untitled

Not only are his photos fantastically evocative but it gave us, the viewers, a chance to hear Steel Pulse's Handsworth Revolution. Peter Mitchell mainly worked in Leeds so using Joy Division (Shadowplay) to introduce his work suggests an oversight somewhere. Still it's a great song and Mitchell's snaps are great too. They're a recording of the changing times he lived through. Lots of demolition work, shops soon to be gone, and regular revisits to a home made ghost train.

Peter Mitchell - Untitled

Peter Mitchell - Untitled

Peter Mitchell - Untitled

Peter Mitchell - Untitled

Major galleries like the Tate were still refusing to buy, or display, photography so in stepped Val Williams. Her gallery in York created an audience for the work and one of the best artists to be enabled by these changes was Fay Godwin. Her 1985 collection, Land, made her name. Beautiful landscape portraits full of awe and longing. Her journeys around these rural parts of the country politicised her. She saw how much of our land had been corralled by the Ministry of Defence during World War II and had still not been returned to the people. Her follow up, Our Forbidden Land, told that story and showed how money and power changed the very landscape we live in. It's just as beautiful as Land but it should make you feel both sadder and angrier at the same time. What a great photographer she is and one I'd never heard of before watching this programme.

Fay Godwin - Land

Fay Godwin - Land

Fay Godwin - Land

Fay Godwin - Our Forbidden Land

Fay Godwin - Our Forbidden Land

Fay Godwin - Our Forbidden Land

I was certainly already familiar with Martin Parr and I've expressed both my doubts, and what I like, about him elsewhere before. As Godwin had shown us how greed and capitalism affects the landscape Parr showed us how it affects us. His 1984 New Brighton series made his name but it also got him, not totally unfairly, accused of snobbery and cruelty. In a possible attempt to redress this he turned his camera on to his own class, the middle class, for a follow up series The Cost of Living (shot in Bristol) which, predictably, is less well remembered. It seems we do prefer to laugh at poor people more than we do rich ones. In the words of a very rich, very unpleasant, man - "sad"!

Martin Parr - New Brighton:The Last Resort

Martin Parr - New Brighton:The Last Resort

Martin Parr - New Brighton:The Last Resort

Martin Parr - The Cost of Living

Mishka Henner doesn't even have a camera. Yet he's still a photographer. In an echo of Fay Godwin he creates works referencing forbidden and restricted areas using computer technology that I don't really understand.

More familiar to us, and introduced by Metronomy, is the hugely successful Instagram. The fusion of social media and photography was bound to happen and it's been picked up, most enthusiastically, by the youth. McCabe interviews committed Instagrammer Molly Boniface, a sixteen year old from Huddersfield, who takes selfies and pictures of her friends. Yet like almost every other photographer in this series, and probably you and I, her most important concern is waiting for the right moment, getting the right light and the correct angle, and getting the best picture she can.

As technology and the times we live in change that never will. This was a fascinating trot through more than a century and a half of British photography and British history. It made me want to go out and take some pictures. What more could I have asked for?

Mishka Henner - Levelland and Slaughter Oil Field

Mishka Henner - Black Diamond

Molly Boniface - Instagrams

Molly Boniface - Instagram

No comments:

Post a Comment