Many friends and family have commented on their displeasure at seeing yet another, presumably highly paid, television presenter being paid to go on holiday and talk about it and I get their point. Also, I'm massively envious. I want to travel up and down the Ganges and tell people what I think about it. I reckon I'd be pretty good at it.

But, here's the twist, so is Sue. She's affable (obvs), she's keen to interact, she's not easily embarrassed, and she manages to eke out stories from those living along the banks of this enormous river while at the same time allowing her own personality to colour the experience. By the end of the three part The Ganges with Sue Perkins I wasn't wishing I'd gone instead of her, I was wishing I'd gone with her. We'd have made great travel companions.

Whereas Levison Wood has the unique distinction of walking most of his epic trips, and Babita Sharma and Adnan Sarwar took a lightly political approach to their recent trips alongside the Indian/Pakistani border, Sue's style of travel journalism is more in the Simon Reeve mould. She simply follows her path, talks about whatever she comes across, and gets involved with the locals. Like Reeve there are nods to geopolitics and ecological issues but this is no lecture and you never feel ranted at. Her jokes are more friendly than they are funny (making up nicknames like Tamsin for donkeys, quoting Eurythmics lyrics), she says 'namaste' a lot, like me she cries at altitude, and she also ponders her life back in London and her father's recent demise. It's hard not to warm to her.

The crisp blue skies and the ice capped mountains of the Himalayas, up by the Tibetan border, where the town of Gangroti nestles must seem a very long way from London. It's the source of the Ganges, a river that Shiva ascribed power when she, the Ganges is always a she, fell from the heavens through the locks in Shiva's hair. For devout Hindus the Ganges has the power to wash away a lifetime of sins (or even more, as we'll find out later).

Worshipping rivers, like worshipping the sun, does make some kind of sense. We need water and heat to stay alive which is not something that could be said for Christian or Islamic deities. But if you're planning on drinking the water to ingest its holiness it'd be best to do that near its source where it's still pure and clear (as evinced by several lingering shots of the river water pouring through fingers or smashing up against rocks), as the Ganges rolls on it collects an awful lot of crap.

Perkins meets a hermit who's lived in a cave for six years but before that was a ballet dancer in Delhi, she witnesses pilgrims whose pilgrimage is being accompanied by the sound of bagpipes, a yogi dude called 'clicking Baba' who can contort his body into some extraordinary shapes, a 90 year old swami who's used photography to monitor climate change and glacial retreat. The characters that Sue meets on her travels will become as much a theme as the river, its sacred nature, and its pollution as we descend into the Gangetic Plain.

The nonagenarian snapper may've written "Oh sky, I love you" on his beautiful shots of the inconvenient truths of the ecological disaster humanity is causing its home planet but, of course, there's a very serious side to all this. If waters start to run dry people will die.

As ever with a travel documentary there's not quite enough time to really get into the meat and drink of this before we're off on our travels again. In Mukhba Sue eats chapattis near a gas bottle and gets fitted out for a sari before heading on to Rishikesh. It's the first proper big city on the Ganges and it's got everything you expect in an Indian city. Cows, monkeys, and people everywhere.

It's where Hindusim has been undoubtedly commercialised (Shiva is the top selling God in Rishikesh), it's where the Beatles came to find themselves (Ringo bought his own Heinz baked beans with him), and it's where Western visitors buy those trousers that tell you they've been to India. Mike Love of The Beach Boys, Donovan, and Mia Farrow all followed in The Beatles footsteps and these days the city isn't shy of branding Hinduism and putting a hard sell on the Ashram detox culture.

It may be a more tourist, than authentic, experience but, by all accounts the food's great and spending a time in a place like this is infinitely preferable to devoting your life to any form of propping up capitalism, either buying crap you don't need to keep up with the neighbours or spending half your waking life in a job you loathe with a boss you loathe for a company you loathe. It's easy to laugh at the holiday hippies but some will come back profoundly changed. As a proud atheist Hinduism makes more sense than any of the Abrahamic faiths to me.

Haridwar marks the point where the Himalayas end and the Gangetic Plain truly begins. Sue meets with Baba Ram Dev, a man who sees no clash of conscience in being both holy and a tycoon. He sells honey and he sells it, specifically, to Hindus. It's special Hindu honey (though what makes it so is unclear) and as we witness Baba Ram Dev riding round on his armed golf buggy we realise the health food business can get as 'tasty' as the honey itself.

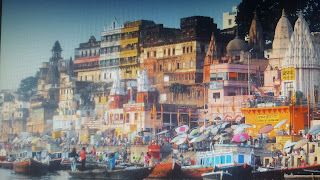

If the popularity of Ayurveda and the evening's blessings down by the Ganges look more the real deal than those of Rishikesh they're as nothing compared to Sue's next stop. The ancient, sprawling, polluted Varanasi. Home to over a million people Varanasi is such an important site for Hindus, and such a vital stopping point along the Ganges, that an entire programme in this three part series is devoted to it.

In this 'intense and beautiful' place the Indians rub the ashes of recently cremated humans into their own bodies, raw sewage flows out in to the Ganges, turds of many types (including human ones) make passing down its alleys a delicate experience, and when the temperature rises, as it often does, to about 47 degrees Celsius you can probably imagine that the whole place stinks to high heaven.

Which is weirdly appropriate as the oldest living city on Earth is, to Hindus, some kind of high heaven. Moksha in Hinduism refers to liberation, release, and emancipation, freedom from samsara, the cycle of birth and death, and it can be achieved best in Varanasi. Each day over 150 human bodies are cremated on open pyres as thousands bathe in the sacred waters as the charred remains of their loved ones float off towards a better place. Or Kolkatta if you're not a believer.

'Standard' barbers can give you a 'standard' haircut so that you can offer your hair to the Ganges. We see young children doing this and in one hilarious, and hopefully not scripted, interchange Sue asks her guide "Is this man a holy man?" to which he replies "No, he's a barber". That sums up the confusion that India can bring to outsiders. Others will find it hard to stomach having open funeral pyres right next to where children are playing. If you're one of them you're likely to find the Aghori sect more problematic still. They eat human remains.

There's plenty to be had for a hungry Aghori. On top of the constantly cremated bodies there are the aftermaths of suicides from the nearby railway bridge. The industrious young boys who use magnets to fish coins out of the river (they've been thrown in as offerings to the Ganges, they're fished out so the kids don't starve) claim they find at least one dead body a day.

If you die in Varanasi you get fast-tracked to the realms of the immortal and that's why so many who believe themselves to be on the verge of death flock there. There are 'death hotels' they can stay in until they pass away. We meet a woman who's been living in one for thirty years, seemingly cheating the grim reaper for a full three decades.

On a motorbike trip to the less populous areas that surround Varanasi we learn about antiquated attitudes to women and see the appalling conditions some people have to contend with in rural India. Male alcoholism, drug addiction, and violence is a very real fear for the women who live here. With no toilets (or even walls, often just a tarpaulin chucked over some sticks) in many houses groups of women can only risk urinating once a day. They go in a group (all decked out in green saris) to guard against getting raped while they're in the fields.

Scorpions, snakes, and insects can be as dangerous as the seemingly ever present threat of sexual violence. A group of students, including some of the motorbike gang, have started to teach the village women self-defence, public speaking, and general assertiveness in an attempt to improve their lot. It'll be a long time but the first step of any journey is always the most important. This was an insight into an India rarely covered on travelogue shows like this and it was, by some margin, the most moving section of the entire series.

So it's a bathetic moment when, back in Varanasi proper, Sue slips and falls in some human faeces. She's visibly distressed (as you would be) but remains in good humour and, in fact, waste, in all its weird and wonderful variety, is what the next section is all about. A boat ride and a chat with a local professor who's dedicated his entire life to trying to clean up the Ganges. The pollution, as we've already established, is shocking but believers consider the river to be 'spiritually cleansing' anyway and that completely trumps any environmental or health concerns. It's as hard for us, with our Western values, to resolve this duality as is it is, perhaps, to understand the families, down by the ghats, who walk round and round the burning corpses of their loved ones hitting the heads of their dead bodies with sticks. It's a confrontation with both death and bodily fluids that in Europe we tend to shy away from.

Patna, capital of Bihar state, is the next stop after the prolonged and emotionally draining week in Varanasi. It used to be the centre of the opium trade but these days it's best known for education. Patna Institute of Technology teaches young women engineering and we meet some of the adorable students who dream of being either train drivers or models and of one day being able to visit London or even Switzerland. If it seems they're making their own decisions in life in a way that just a few years ago they might not have been then that's not true in every aspect. Their parents will still dictate who they marry.

With the rice paddies and agrarian heartlands that surround Patna it seems someone involved in agriculture will make a good match for these young women (or their parents at least). Perhaps someone from Daveshpura, the 'miracle village' where the 'world's best potato farmer' lives.

At Patna the Ganges splits in two. The main part courses through Bangladesh but as this is primarily a show about India we follow the waterway that becomes known as the Hooghly down to Kolkata, behind Mumbai and Delhi the third most populous city in the whole of India with a metropolitan area of over 14,000,000 people.

Sue's been to Kolkata before, two years ago, to make a radio programme. There she met up with a young street kid, Rakhi, who'd fallen under the protection of The Hope Foundation who provide shelter, food, and safety for kids sleeping rough in the city. At the age of nine Rakhi was bubbly and confident and spoke of wanting to become a doctor.

By the age of eleven she was distracted, nervous, and particularly uncomfortable when men were in the room. Only eleven years old and she's had her youth stolen and hers is surely only one of thousands of similar stories across the place that locals, surprisingly given these facts, call the City of Joy.

Of course like anywhere there are joyful aspects to Kolkata life. Not least the baby showers that traditionally begin with a visit by a group of Hijra. Hijra are groups of transgender individuals who'd been born with male genitals but have since rejected any gender and have, in recent years, been accepted by law as a third gender.

They dance, sing, and chat at baby showers as well as christenings, weddings etc; and they dispense blessings for cash. The Hijra we meet are a family, a pretty unorthodox one for sure, but a family. They all live together, forty of them, in a big yellow house that is dripping with gold ornamentation inside. It's garish but it looks like fun. Of course like much fun it masks sadness. The law may've recognised them but many more conservatively minded Indians still fear and/or despise them and, in many cases, they've been rejected by their birth families.

They may, in modern parlance, be fierce but our next stop sees something much fiercer. The vast forest of Sundarbans on the Bay of Bengal is the world's largest river delta and at the Sundarbans Tiger Reserve we see the tiger patrol in action, up to their hips in Gangetic mud, maintaining 96 kilometres of fencing so that poachers can't get in and tigers can't get out.

The pace of life is slow down on the mangroves even though 4,000,000 people live in the Indian part of Sundarbans alone. Some have been given permits to fish in the tiger reserve and they relate experiences of tigers leaping out of the waters and on to their boats. It's said there is at least one fatal tiger attack in the region each and every week.

They're not the only threat. The king cobras that live there can, and often do, kill people. With these deadly dangers so imminent it's perhaps unsurprising that both the Hindu and Muslim population of Sundarbans worship Bonbibi, the guardian spirit of the forest, whose motto is "take only what you need and you'll thrive, take too much and you won't survive".

It's hard to imagine how 6,000,000 people could do anything but 'take too much' but, sure enough, that's the number of visitors that come to a grand Hindu festival at the point where the Ganges meets the sea. After the Kumbh Mela (which also takes place on the Ganges but only once every twelve years) it is the world's largest gathering of humanity.

If you take to the Ganges during one of these festivals not only do you absolve yourself of a lifetime of sins but retroactively you absolve the previous fourteen generations of your family of all their sins too. That's why they call it/her sweet mother Ganga and that's why people travel so far to partake. Naked holy men who've rejected clothes to be closer to Shiva have travelled down from their homes in the Himalayas to sit with their dicks out, smoking industrial quantities of weed, in what appears to be some kind of freakshow but turns out to be just another day on the banks of the beautiful, crazy, dirty, endlessly fascinating Ganges.

It doesn't matter if you're a dying person hoping to achieve moksha, a Himalayan holy man with your cock out, a hungry tiger, Ringo Starr with a tin of beans, a bagpiper, or a presenter of The Great British Bake Off - there's something in the Ganges for you. There certainly was for me.

No comments:

Post a Comment